In this way, God chose to come

I had great joy in a three-week period this past summer to offer blessings soon after the births of three babies. It’s one of the highlights of my priestly ministry, to be invited to come into a hospital room and be with a new family, new parents, as they rejoice over the gift of a baby they’ve received, to pray with them, to share their joy, their hopes, their exhaustion, and yes, some of their apprehension. For all three families, it was their first child. I could see in the parents’ eyes their wonder, amazement, and love. Although extended families gathered around and they were all in the care of excellent hospitals and medical professionals, I could also sense the awesome responsibility that the parents felt.

As I’ve been talking, many of you will recall your own experience in hospital rooms like that, a few years ago, or perhaps decades ago. Some of you will be hoping for similar experiences in the near or not-so-distant future; and some of you may feel sadness that this is something you will never know personally. Whatever our individual experience may be, we know about the happiness and responsibilities, the joy and the heartaches, that come with newborn babies.

I encountered other babies over the last few months; babies that whatever the circumstances of their birth, were now living with their mothers on the street, or nearly so. Three or four months old; their mothers had come to me for help, for housing, or gas, or food. I could see in the faces of those mothers the same love I saw in the faces of the parents in those hospital rooms; the same hopes for the future. But what I saw most was worry and fear. Like most of you, when I encounter mothers and babies in these circumstances, I feel great compassion and sorrow, but that’s also often tinged with a little judgment, as I wonder what brought them to this place in life. I give them what financial help I can thanks to the generosity of members and friends of Grace, and I also try to point them in the direction of agencies that might help them with some more permanent solutions.

Tonight, at Christmas, we encounter another mother and baby, one whose situation is much more similar to those babies in need that I just described than the newborns I met in the hospital last summer. Mary and her husband may not have been homeless in our contemporary sense, but that night they had to find shelter in a stable, or more likely, a cave.

Mary was pregnant under suspicious circumstances—although she and Joseph were legally married according to Jewish law, the contract or marriage license had been signed, their relationship had not been consummated. According to that same Jewish law, Mary’s pregnancy meant she had committed adultery, and Joseph was legally obligated to divorce her. Mary’s pregnancy brought public shame on her and on her husband.

These are things we tend not to think about when we hear the familiar story of Jesus’ birth. Most of us know it so well, and if we haven’t heard it many times before, we probably still know its basic outline—a manger, a stable, no room in the inn; Mary, Joseph, the baby, shepherds, angels, all of that. We know it but we tend to overlook its messiness, the embarrassment of it all. It is a messy and embarrassing story in spite of everything we do to sanitize it and sentimentalize it.

Our images of Christmas are dominated by paintings like the reproduction on tonight’s service bulletin, crèches like the one that stands before our altar. Mary is young, beautiful, well-dressed; Joseph looks distinguished, mature, an upstanding member of the community. Except for the crude surroundings, things are serene, respectable, beautiful.

The reality was rather different. Mary was young, uncomfortably young by twenty-first century standards, her reputation in danger because of her pregnancy. Joseph too was disreputable, if not already, then he would be by deciding to stay with her. They were not from Bethlehem. They had come here because of imperial fiat, a distant and ruthless ruler imposing its whim on subject peoples. The shepherds who came to worship were even less respected than Mary and Joseph may have been; virtual outcasts living on the edge of society obeying none of society’s norms.

Here, to this place, God chose to come. To a tiny village, a manger, a feed trough in a troublesome backwater province of the greatest empire the world had ever seen.

Here, to this couple, God chose to come. To a young girl and her husband. We wonder about them. Christians have pondered the mystery of God becoming flesh through Mary. We have argued and debated; we have painted, and played music, and sung and prayed to her. We have imagined all manner of things about her. But what we can know is that when word came to her that she would have a son; when God chose her, she said yes. We don’t know much about Joseph other than his name and occupation. We don’t know how old he was; we know he was righteous—the Gospel of Matthew tells us that—and we know that when word came to him that Mary would give birth to God, Joseph said yes. To this couple, God chose to come.

Here, to this newborn infant, God chose to become flesh. If you’ve ever seen a newborn, if you’ve ever seen your own newborn child, you know about the beauty, love, excitement of a new baby. You also know about their weakness, vulnerability, their complete and absolute dependence on others for everything. Without the help of other humans, a baby will die in a few minutes or hours. They are utterly helpless. They are weak and needy and messy. In such a form, in such a body, God chose to become flesh.

The miracle of Christmas is not just the lovely story. In fact, the miracle of Christmas has nothing to do with virgin birth, or shepherds or wise men or angels. The miracle of Christmas is that in that newborn baby, we see God become human, God become one of us. In the vulnerability, weakness, utter dependence of that infant, we see the face of God. The miracle of Christmas is also that in two quite ordinary people, in Mary and Joseph, in two ordinary people who chose to say yes to God, we learn something important about the nature of faith.

That’s the miracle of Christmas, the miracle of Christianity. The God we worship is not a god of thunder resident on a high mountain. Nor is the God we worship a god who demands we bow to him because of his vast superiority. Our God is a God who created us, knows us, became one of us. The God who created us, knows us, became one of us, that very God chooses us.

We may encounter God or the presence of the divine in all manner of things—the beauty of nature, or of music or art, in a place that is sacred to us or sacred to a memory. None of that is beyond the possible. But our faith proclaims that we encounter God most certainly, most completely in the one who was born in Bethlehem, walked the dusty roads of Palestine, was crucified by Romans and was raised from the dead.

Our faith proclaims that we encounter God most certainly and most completely in a human who was born like us, lived like us, suffered like us and died like us. That’s the mystery of Christmas, the mystery of our faith.

We see the burden and the joy of that faith, the mystery of our faith in that couple as they wrap the newborn in swaddling clothes and lay him in a manger. We sense the burden and joy of our faith, the mystery of our faith as the gospel tells us, “and Mary treasured all these words and pondered them in her heart.”

We cannot hope to comprehend or make sense of God becoming flesh in a newborn babe. We cannot hope to understand why or how or to what end. What we can do is treasure and ponder. We can respond to the needs of those in whose faces we see the face of Jesus Christ; we can wrap them in swaddling clothes and embrace them with the love of Christ. And above all, we can open our hearts and say yes when God asks us to bid God welcome.

May your hearts be filled with the joy and love of Christ, and may you share that joy and love with all those you encounter today and in the days to come.

Merry Christmas!

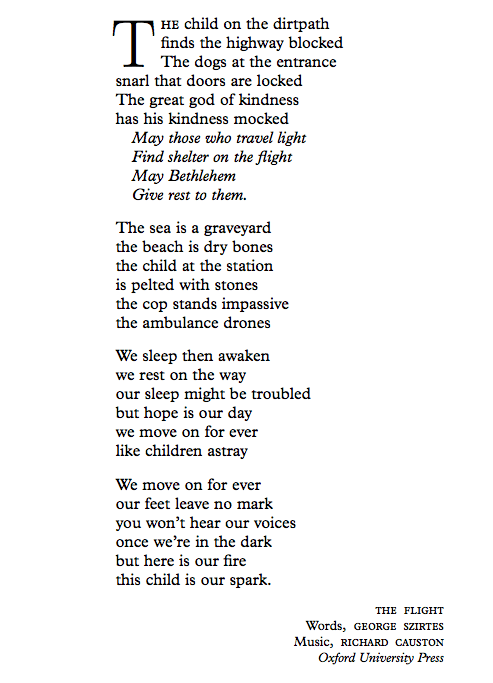

For more on the carol, and the poem, go to: http://www.kings.cam.ac.uk/news/2015/causton-carol.html

For more on the carol, and the poem, go to: http://www.kings.cam.ac.uk/news/2015/causton-carol.html