In addition to today being the Wisconsin Ironman Triathlon, it is in church parlance, the beginning of the program year. Our choir is back after its summer hiatus and Christian education for children and adults begins as well. This week, we are beginning something we’ve not done in quite some time at Grace, at least not on a regular, consistent basis. We will be offering two bible studies—one begins today, between the services; the other takes place on Thursday evening at 5:30. I hope some of you will take advantage of these opportunities, for engaging more deeply with scripture is essential to deepening your faith and your experience with Jesus Christ. Continue reading

Tag Archives: sermons

Pure and Undefiled Religion: A Sermon for Proper 17, Year B, 2018

Religion that is pure and undefiled before God, the Father, is this:

to care for orphans and widows in their distress, and to keep oneself unstained by the world. (James 1:27)

What is pure and undefiled religion? What is religion? You might be surprised to know that this latter question is one that is much debated among contemporary scholars of religion. There’s an overwhelming consensus that what we in the west call “religion” and which we distinguish from other areas of life and culture, is very much a modern western concept that has been imposed on other cultures and peoples. So, for example, there is no term for religion in the languages of India, and when the British Empire came to the subcontinent, it categorized a certain number of activities and practices as religious and defined Hinduism as a religion.

No doubt you find it odd that I might begin a sermon by questioning the term religion. It very likely is, but as many of you know I was a professor of Religious Studies for fifteen years before becoming a full-time parish priest, and as a teacher and scholar, I was very much interested in the way scholars and ordinary people thought about the material I was teaching and studying How we as a culture define religion has an enormous impact on how we organize society and its institutions, how we negotiate among competing claims and values (think “church and state” for example, and how we regulate individual and community behavior. As individuals, how we define religion for ourselves, shapes not only our self-understanding, but helps to shape our identity as individuals and members of larger groups, and where we place our ultimate trust and value.

When I taught Intro to Religion, I would usually begin the first day by distributing to the students a handout with around 15 definitions of religion, derived from theologians and scholars of religion, anthropology, and sociology. It was an exercise intended to get students thinking about this cultural activity we call religion, and to challenge the way they thought about it. So, for example, the image posted above, the scene outside the church today, where we have a shrine erected to Wisconsin’s true religion.

I know this sounds all terribly abstract, but let me point out something important. The word “religion” in the verse I quoted a few minutes ago actually means devotion or worship. That puts a rather different spin on things, doesn’t it? “Worship that is pure and undefiled before God is this: to care for widow and orphans, and to keep oneself unstained from the world.”

That translation may be more puzzling than clarifying, because to us in the 21stcentury, none of that, caring for widows and orphans, or maintaining purity from the world, sounds like worship to us. Ethics, morality, maybe, derived from prior religious beliefs, but certainly not worship. I’d wager that when most of you heard that verse the first time, you got all excited, because James confirms the views of most progressive Christians. What matters is justice, outreach, advocacy for the poor and the oppressed, challenging new immigration policies, all of that.

The terms pure and undefiled, even unstained strike us strangely in our contemporary world, even if in the case of their appearance in the Letter of James, we can easily interpret them in ways that make them less, indeed even support our own personal preferences and commitments. When we see the same English word in the verses from the gospel of Mark that we heard this morning, we may have a slightly different reaction.

After all these weeks, we’re back in the gospel of Mark, where we will remain for the rest of the liturgical year, until the end of November. To recap a bit, so far in Jesus’ public ministry, we have seen him heal a number of people of their diseases and infirmities, cast out demons, walk on water, calm storms, and feed five thousand people. We haven’t been introduced to much of his teaching or preaching, one or two parables and that’s about it. As fast-paced as Mark is, the gospel will pick up in speed and intensity as we move inexorably toward Jesus’ final confrontation with the Roman authorities and their Jewish sycophants in Jerusalem. And in today’s reading, we see another aspect of the conflict between Jesus and other Jewish communities and leaders.

What’s at stake here, as it almost always is when Jesus is in conflict with other Jews in the gospels, is the interpretation and authority of Torah, Jewish law. The Pharisees were a group within Judaism that sought to extend the role of Torah to the daily life of ordinary people. Their interpretation of Torah was intended to offer guidance in what to do so that the central precepts of Torah were maintained. They called this “building a wall around Torah.” Take the 10 commandments: “Remember the Sabbath Day and keep it holy.” Well, that’s great, but what does it mean to keep the Sabbath Day holy? The Pharisees explained that by offering guidance on what constituted work, and how much work one could do on the Sabbath.

In today’s gospel, the issue at hand is hand-washing. The Pharisees understood ritual hand-washing as keeping oneself ritually clean before eating; other Jewish groups saw things differently and Jesus’ disciples, apparently, couldn’t be bothered. It’s worth pointing out that the word translated as “defiled” here is a different word than the one used in James. Here, the word literally means “common” as distinguished from “sacred” or set apart.

Jesus’ answer, as it so often does, changes the terms of the debate. The issue is no longer whether or not to maintain ritual cleanliness, but the deeper meaning of defilement, or being “set apart.” Jesus points out that what matters is what is in the heart, not the particular ritual action, and here he lists all the ways in which we might defile ourselves by our thoughts.

And that may be where we come back to the letter of James and to our own context. In addition to the two funerals that played out in front of mass audiences over the last two days, religion has been very much in the news the past few weeks. There was the spectacle of a White House dinner for key evangelical supporters of the president early in the week; and the ongoing and deepening crisis in the Roman Catholic Church.

In the former case, many people question the political choices of many Evangelical leaders. In the latter case, that of the Roman Catholic Church, with the crisis and cover-up extending to the highest levels of the Church, the institution is shaking to its very foundations, and the faith of many ordinary Catholics is wavering.

We might think that none of this matters to us here. But it does. All of it affects the general perception of Christianity in America and attitudes toward the institutional church. And we in the Episcopal Church are not immune either from the sin of sexual misconduct and cover-up or the temptation to cozy up to power and privilege.

The world is watching. As we struggle to make sense of what’s happening in this nation and around the world, as we struggle to find our own way in these difficult times, James offers us some simple advice. He reminds us where our focus should be and what the pitfalls are. It’s easy to look in a mirror, he says, to focus on ourselves, instead of looking to God. We should avoid criticizing others. He says that unbridled speech is worthless religion: good advice in the face of the noise, hate, and anger all around us now, that too often escalates from rhetoric to hateful action.

And he reminds us of our duty to care for the marginalized: widows and orphans, yes; but also all those who our society despises, rejects, and leaves behind. And finally, he admonishes us to keep ourselves unstained by the world. It may be unfamiliar, troubling language, but it’s worth exploring whether even this might provide us with guidance. Can we, by our actions, our words, our disposition, bear witness to the love, grace, and mercy of Christ, to a world that too often sees Christians and Christianity in very different terms. Can we, by our actions and words, change our homes, neighborhoods, and workplaces for the better?

Where would we go? A Sermon for Proper 16, Year B, 2018

There’s something about natural disasters that brings out the best in people. Of course there are always scammers, those who seek to take advantage of vulnerable people but the reality is that we tend to come together when we are faced with difficult situations brought about by events that are out of control. We help each other, but we also want to share stories, tell of our experiences and listen as others share their experiences as well. We do it on social media but we also do it when we’re going about the daily business of life. We chat with cashiers or fellow customers about what we’ve seen and experienced, and what’s happening elsewhere. Many of us also volunteer, filling sandbags, or helping to clean out neighbors’ or family members’ basements after the flood.

Such spontaneous community is increasingly rare in our society and culture. In our divided nation, and with the fragmentation brought on by the many cultural changes that we’ve seen over the last decades, it often takes a natural disaster like a flood to draw our attention away from the immediate concerns of our own lives and focus for a time on the larger questions and larger drama of human existence.

As we have read John 6 these last few weeks, we have seen a somewhat similar dynamic play itself out. The chapter begins with the miracle of the feeding of the 5000. Imagine the excitement, the conversations among those who experienced the miraculous appearance of food. Imagine the stories they would tell to their children, grandchildren, neighbors and friends!

But the scene and the energy quickly shift. We see dialogue, conversation, and finally, conflict, as Jesus’ dialogue partners become increasingly critical of his statements. And now finally this:

Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood abide in me, and I in them.Just as the living Father sent me, and I live because of the Father, so whoever eats me will live because of me. This is the bread that came down from heaven, not like that which your ancestors ate, and they died. But the one who eats this bread will live for ever.’

We’re told that the scene has shifted in another way. Whoever Jesus had been talking with earlier in the chapter—when was he addressing the whole crowd? And when did it become a smaller group? Now he has moved into the synagogue and is speaking with the congregation gathered there.

And another set of characters is introduced—the disciples. So the group of those with whom Jesus had been talking has become smaller, more intimate, more deeply connected with Jesus. They were those who had been following him since the beginning, or had joined the group along the way somewhere. But this is a hard saying—it’s more than a “hard saying” it’s a scandal, an offense, the Greek word from which we derive scandal is used here.

So some of them turn away—not the vast crowd that had been fed bread and fishes; nor even those who had listened to Jesus speaking in the synagogue. Now, some of those who turned away were his disciples—men and women who knew him, had followed him thus far, had listened and learned. But the circle grows even smaller. Jesus gathers his closest companions to him, for the first time in the Gospel, there’s a reference to the “twelve.” It’s a term that appears very infrequently in the Gospel of John. Jesus turns to them and asks: “Do you also wish to go away?”

In the last two verses of the chapter, there’s an ominous note-a reminder that not even the twelve could remain with Jesus to the end—The gospel writer mentions Judas by name and his betrayal of Jesus.

The reference to Judas is a reminder to us that when Jesus speaks of his body and blood, he is not speaking only of the Eucharist, but also of his crucifixion and resurrection. It’s no accident, nor is it insignificant that in our Eucharistic prayers, going back to Paul’s account of it in 1 Corinthians, we begin the words of institution with “On the night on which he was betrayed, Jesus took bread…”

But there’s more for us to think about here. Jesus is not speaking only of the Eucharist. He is also speaking of himself. Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood, abide in me and I in them. Discipleship in the Gospel of John is about relationship with Jesus. Throughout the gospel, from the very first chapter, those who follow Jesus are invited to abide with him, to be with him.

In today’s gospel, Jesus’ listeners are presented with a choice. They can turn away or reject him, or they can listen to him, hear his words, and follow him. It’s not a yes or no choice. After some of those who had followed him walk away, Jesus asks those who remain, “Do you also wish to go away?”

Peter’s answer isn’t yes or no. Having walked with Jesus thus far, he can’t imagine life without him. “To whom can we go? You have the words of eternal life.” Peter has already experienced relationship with Jesus, abiding with him, and the prospect of life without him is incomprehensible. Jesus’ words are eternal life; his words are spirit, all else seems empty in comparison.

Now the Gospel of John has the characteristic that simple ideas, words, concepts can suddenly seem to be remotely abstract, foreign to our experience and lives. Spending time in the gospel of John can be disorienting and alienating. The words wash over us. We have, after all, been spending five weeks hearing this chapter from John’s gospel. If you read it through in one sitting, it comes across as repetitive, to some, even nonsensical. Many of us, including your preacher, will be happy to return to Mark next week, whose language and message is much clearer, though perhaps equally difficult to make one’s own.

What matters above all in John, once we cut through the verbiage, is relationship. What matters is the life-giving relationship with Jesus Christ, offered by Christ. What matters is the experience of abiding with him as he abides with us. John is trying to help us understand, but more importantly to experience, the life that he experienced with Jesus Christ. All of the language, all of the discourses, all of Jesus’ miracles, are directed toward this.

Most of us struggle with our faith. Most of us wonder at times, if God exists, whether Jesus was the Son of God, or whether he truly was raised from the dead. We wonder about heaven and hell. We have lots of questions, doubts, uncertainties. Some of us probably aren’t even sure why we bother coming to church. Does any of it matter? Is any of it true?

But there is something that draws us here, something that speaks to our deepest yearnings and hopes. We might not even be able to articulate or name what it is. We come here and find something. For the Gospel of John, what we find here is relationship, life. We experience in the community gathered, in the bread and wine, in the word read and proclaimed, in all of that, we experience life. Jesus offers us that life. He invites us to stay, to abide with him, to live in him as he lives in us. When we say yes to him, we are not proving an argument or saying yes to a proposition. We are inviting and experiencing relationship. When say yes to him, we say yes to life.

Snatched up by the Spirit: A Sermon for the Fifth Sunday of Easter, 2018

This is one of the weeks of the Eucharistic lectionary when I have had to struggle extensively as I prepared this sermon. My struggle wasn’t with the dearth of material—over the years I’ve preached on both today’s gospel reading and the story of Philip and the Ethiopian Eunuch. And as you know, I have a particular fondness for the Gospel of John, for vineyards, and for that good old word “abiding, so I began working on the gospel reading, and was thinking about including a hefty dose of material from the epistle reading as well.” But I was struggling because I was trying to discern which direction to go, what the Spirit is saying to our church, Grace Church today. In fact, as I prepared for the Wednesday eucharist at Capital Lakes, I decided to focus on the gospel and epistle reading. A member who attended that service, joked that he enjoys seeing how my thoughts develop from Wednesday to Sunday. Well, he’s I for a surprise today. Continue reading

A Broken Nation, A Broken World, Our Broken Hearts: A Homily for Ash Wednesday, 2018

There may be no day quite like today. It is a day on which the church observes one of its most solemn days, certainly its most penitential days as we mark our foreheads with ashes and begin the season of Lent. All the while, around us in the secular world, and in our own lives, many of us will go about the business of Valentine’s Day, celebrating love and relationships, enjoying romantic dinners, and above all, chocolate.

And while our minds may be elsewhere, thinking of Valentine’s hearts, in a few minutes we will read together the words of Psalm 51:

“The sacrifice of God is a broken spirit,

a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.”

There’s nothing wrong with that juxtaposition. There’s nothing wrong with coming here on this day, reciting the powerful words of the litany of repentance and Psalm 51, hearing the words that I will say, “Remember that you are dust and to dust you shall return,” and returning to your daily lives and relationships. We live complicated and conflicted lives and even as we seek to grow spiritually, we also have jobs, and families, and relationships, and other matters that demand our attention and time.

I began writing this homily yesterday and continued working on it this morning, thinking about the challenges of understanding ourselves as we stand before God on this day. We are called to remember who we are, that we are dust and to dust we shall return, that we are created by God, in God’s image, yet that we experience ourselves as fundamentally broken, far short of the human beings God intends us to be, needing not only to confess our sins and repent, but to experience God’s never failing grace and mercy, and God’s power to remake us, recreate us, in God’s image. To use the language of Psalm 51 that we will recite in a few minutes:

Purge me from my sin, and I shall be pure,

Wash me, and I shall be clean indeed;

Blot out all my iniquities,

Create in me a clean heart and renew a right spirit within me.

I was writing these words, pondering the meaning of this day as I heard reports of yet another mass shooting at a school in Florida. According to the Gun Violence Archive, this is the thirtieth mass shooting in the US this year, the 9th mass shooting at a high school.

And as I reflected on this horror, on our willingness to stand by as we watch the carnage, I turned from the penitential psalm 51, to the more ominous words of Joel. We are, as a nation, a culture, a people, at, or even beyond, a turning point. With the violence and hatred in our midst, the racism, the attacks on immigrants, the sexual assault allegations that have struck at Hollywood, Corporate America, the Church, and yes, the White House, we are witnessing the collapse not only of our institutions, but of our moral fiber, our civil society. We have never been in more need of the message of Ash Wednesday, never more in need to be honest with ourselves as individuals and as a nation, that there is evil at our very heart, evil we need to repent and turn away from.

There are in these two readings two very powerful verses that move me deeply—the first is from Joel,

“Between the vestibule and the altar

let the priests, the ministers of the Lord, weep.”

There have been times over the years that I have been nearly in tears as I approached the altar—times of personal crisis, tragedy in our congregation or in my own family. But more often I have been near tears because of events in our community, nation, or world. Sometimes, the tears were tears of grief or mourning, often, especially recently, they have been tears of anger and frustration. Such tears can be a sacred response to events in our lives and world—the tradition of lament, of calling out to God in times of distress, and giving voice to our doubts, fear, and anger is one of the most familiar forms of the Psalms. We see some of that language here in Psalm 51.

But the other powerful verse that has deeply moved me over the years, perhaps entered into the marrow of my faith, my understanding and experience of God, is from Psalm 51:

Make me hear of joy and gladness, that the body you have broken may rejoice.

For me, this verse speaks not only of suffering and lament, of the consequences of sin, and the effects of punishment, but that in the crucible of this experience of sin, repentance, and forgiveness, we come, at the end to a place of joy and gladness, having experienced the miracle of God’s forgiveness, grace, and steadfast love.

We lament a nation that will not protect its children from the gun violence and hatred. We mourn the senseless and meaningless of so many; grieve the trauma of those who survived shootings and will be forever marked deep in their souls by the horror. There is so much in our world and nation that we regret, and mourn, and lament.

Sometimes, our faith falters, we wonder whether God still hears our prayers or acts in our world. Sometimes, our words seem empty, our gestures meaningless, the knees we bend in supplication futile attempts to invoke God’s mercy and action. Sometimes, perhaps most of all today, we identify with those hypocrites whom Jesus criticizes for making a show of our fasting, for drawing attention to our almsgiving, for praying publicly and loudly.

This day, of all days, calls us to remember—who we are, where we came from, whose we are. Today is a day to remember that we are dust and to dust we shall return. Today is a day to lament, and weep, and mourn, a day to grieve for the dead and injured, to pray for those whose lives have been shattered by gunfire.

Today is also a day to repent, to ask God’s forgiveness and to experience God’s love, grace, and mercy. I hope that this evening as we remember that we are dust, and ask God’s forgiveness for our sins, that we experiencing the transforming power of God to remake us in God’s image that our broken bodies may rejoice.

May this day, may this Lent be a time when we experience anew God’s power to transform and change us, and being changed, may we help God bring change to this broken and sinful world.

You are God’s beloved child: A Sermon for the Baptism of Our Lord, 2017

A friend of ours, our former Yoga teacher, was back in town over the holidays, and over lunch as we caught up on our lives, she recommended a book to me: Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion. It’s written by Fr. Greg Boyle, a Jesuit priest who has served in the LA projects for over 30 years. He works with gang members, helping them get off the street and leading productive lives. It’s a book full of powerful stories of redemption, forgiveness, resilience, and suffering. For most of the men and women in these neighborhoods, gangs provide the only family and community they have ever known. Continue reading

God is with us: A Sermon for Christmas Eve, 2017

Is there anything quite so wonderful as a Christmas Eve service? The church is decorated beautifully with poinsettas and wreaths and greenery. Our beloved and beautiful crèche stands where it does each year at the foot of the altar, with its wonderful hand-carved figures. We have heard our choir and organ perform music familiar and new. Some of us have already begun to celebrate Christmas, having come here from parties or gatherings. Others are looking forward to late night festivities, or to lavish dinners tomorrow with friends and family.. Continue reading

Being Witnesses: A Sermon for the 3rd Sunday of Advent, 2017

In these dark days of Advent, as the days grow shorter and the sun’s light grows dim, the mood of our nation and our world seem very much in synch with the season. It’s difficult for us to ignore all that is occurring around us and focus on the season of Advent, and the coming of Christ at Christmas. Sometimes I feel as though the festivities and hoopla, whether it’s the parties we throw or attend, or the glitz of stores and the blitz of marketing are all intended to distract us from what’s happening—global warming, the threat of nuclear catastrophe, the continuing assault on our constitutional liberties, on democracy itself.

It’s hard to find our way through it all, it’s hard for us to find perspective, to keep our faith when there is so much profoundly wrong and unjust, and the forces of good seem impotent in the face of the evil that surrounds us.

On top of it all, many of us struggle to make sense of, let alone, proclaim, the message of Jesus Christ in this context. When Christianity has been coopted by extreme nationalists and white supremacists, when there seems no connection between the message of love, peace, and reconciliation proclaimed by Jesus Christ, and the dominant voices of Christianity in America, we may want to hide our faith, to keep quiet. We fear being associated with the Franklin Grahams and Roy Moores and silence our voices, out of fear that we might be accused of supporting them. Let me just add, if you are not deeply troubled by the cooptation of Christianity by a certain political agenda in this country, you should examine your beliefs and commitments, for the very soul and future of Christianity is at stake, the gospel is at stake.

Our lessons today remind us of where our focus should be, where and how we should proclaim Christ, where and how we should work for justice.

The reading from Isaiah, the first verses of which provide the text for Jesus first public proclamation in the Gospel of Luke, offer both reassurance and command. As Christians, we read these words as promise of Christ’s coming, of the future reign of God that he proclaimed and for which we hope. We see ourselves as recipients of that good news, and of the promised healing and release.

At the same time, we must see ourselves in this story, not just as recipients of God’s grace and justice but as participants in the coming of that justice. We are called to rebuild the ruined cities—and here we might think not only of literal cities, but of all the ways that human community, the common good, have been undermined and attacked in recent years.

Even stronger are the words from the Song of Mary. It’s always helpful to remember just who she was—a young woman, likely a teenager, mysteriously, shamefully pregnant, as vulnerable in her historical context as a similar young woman would be in our day. Yet from that small, unlikely, reviled person, comes this powerful hymn that witnesses to God’s redemptive power:

My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord,

my spirit rejoices in God my Savior; *

for he has looked with favor on his lowly servant.

From this day all generations will call me blessed: *

the Almighty has done great things for me, and holy is his Name.

He has mercy on those who fear him *

in every generation.

He has shown the strength of his arm, *

he has scattered the proud in their conceit.

He has cast down the mighty from their thrones, *

and has lifted up the lowly.

He has filled the hungry with good things, *

and the rich he has sent away empty.

This familiar hymn has suffered for its popularity and familiarity. Its use in worship over the millennia has numbed us to its revolutionary power. We need to reclaim it today, sing it with meaning. We need to do more than sing it, we need to work so that it comes into being. We need to imagine the possibility that God is working in this way, in spite of all evidence to the contrary, in spite of all our fears, doubts, and despair. We need to believe that the words of a first-century teenaged single mom can inspire to see God at work in the world around us. For remember, the world in which she lived was unjust and violent as well, and for many people hopelessness and terror were ways of life.

And finally, the gospel…

We heard the story of John the Baptizer from the Gospel of John. It’s a brief excerpt of a larger narrative, and on the surface it’s rather strange, although you might not have thought anything odd about this when hearing it. In the Gospel of Mark’s description of John that we heard last week, the focus seemed to be on his lifestyle, his clothing and diet choices (camel’s hair, locusts and wild honey). According to Mark, he preached a message, “Repent for the kingdom of God is at hand.”

Now in John’s gospel none of that is present. While some of his preaching message is consistent, at the heart of John’s portrayal of John is something else, the fact that John was a witness to Jesus Christ. In a rather odd formulation, John writes that “

This is the testimony given by John when the Jews sent priests and Levites from Jerusalem to ask him, “Who are you?” He confessed and did not deny it, but confessed, “I am not the Messiah.”

For that is John’s purpose and role in the fourth gospel—to point toward Christ. John is a witness, the witness. And more than witness, for the Greek word behind the English “witness” and “testify” in the first few verses of the reading is word from which we get our English word “martyr.” John came to bear witness to the light, to testify about Jesus Christ. Later in the first chapter, John sees Jesus passing by, points to him, and tells several of his disciples, “Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world.” The disciples then leave John and follow Jesus.

These are questions of identity and purpose. The priests and Levites asked John who he was, in a scene that is reminiscent of the scene in the synoptic gospels where Jesus asks his disciples who people say that he is. John directs their attention away from him toward Christ.

John offers us an important lesson, not just about who he was and who Jesus Christ is. He also reminds us that one of the most important things we do, in our words and in our lives, is point to Jesus Christ. It is in and through us that others learn what it means to follow Jesus and also learn Jesus’ message of love, peace, mercy, and justice. In this time, when so many others proclaim a different gospel, and very different message of Jesus, our witness to him is more needed than ever. May we witness, testify, and point, clearly, unequivocally, and boldly, to the Jesus Christ who stands with the poor, the oppressed, the captive, and the God who casts down the mighty from their seats and fills the hungry with good things.

Questioning God, Called by God: A Sermon for Proper 17, Year A, 2017

Last Sunday, Jesus asked his disciples two questions: “Who do people say that I am?” And “Who do you say that I am?” I invited you to reflect on those questions and am looking forward to hearing from some of you what you’ve thought as you’ve wrestled with them. In today’s reading from the Hebrew Bible, Moses asks God a question. At its heart, it’s a simple one: “Who are you, God?” But God’s answer is anything but simple and opens up to us an infinity of questions. In a few minutes I will invite you to follow Moses’ lead and ask questions of God. But first, let’s explore the text. Continue reading

God tested Abraham: A Sermon for Proper8, Year A 2016

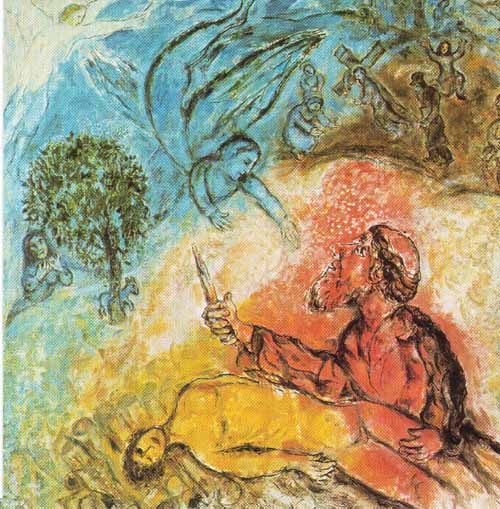

Marc Chagall, The Sacrifice of Isaac, 1966

We’ve been reading the story of Abraham these past few weeks, and today we hear the most dramatic episode in his story. Indeed, this may be one of the most dramatic stories in all of scripture. It confronts us with a horrific dilemma and its implications concerning God’s nature and the nature of the relationship between human beings and God, the nature of faith, are deeply unsettling. Continue reading