December 25, 2023

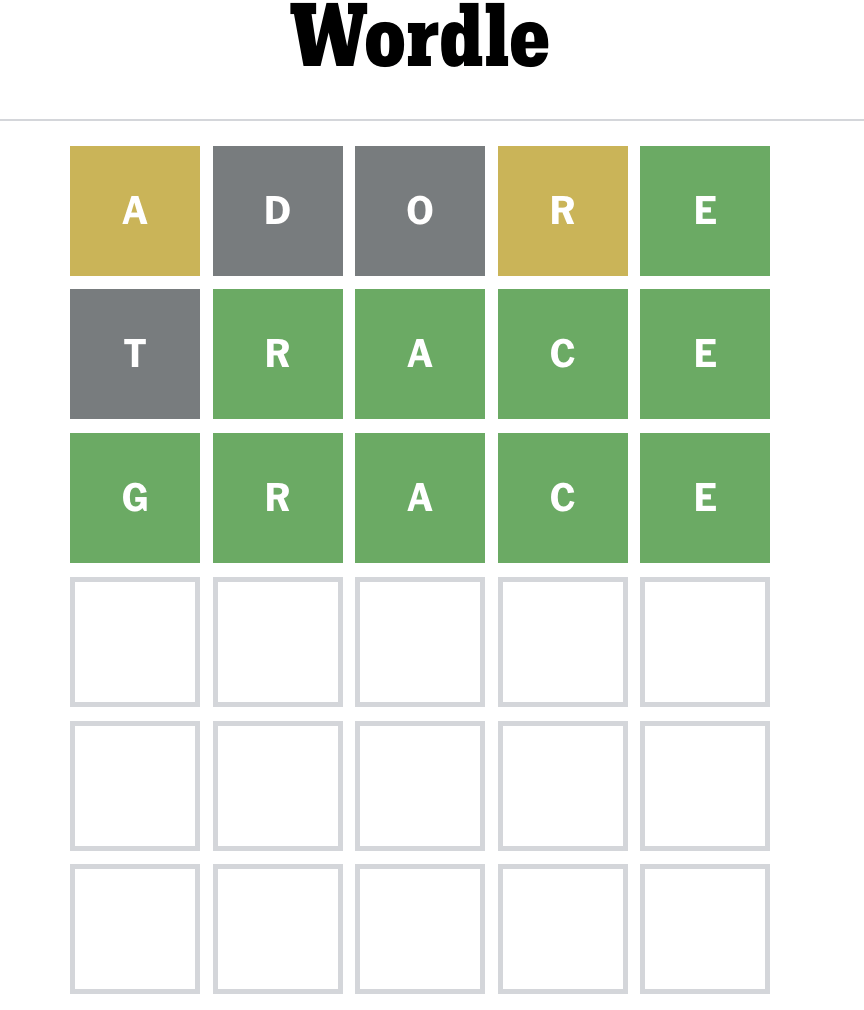

Do any of you know the New York Times word game “Wordle”? It became an internet sensation during the lockdown. The goal is to guess a five-letter word and you have 6 chances. It’s rather addictive, and for many months, everyone would post their results on social media. That’s become somewhat less common over the years, but yesterday, a former parishioner emailed me his results. On the third try, he got it “GRACE.” Over the course of the day, and night, yesterday, others mentioned it to me as well.

Yes, I do it, but I’m rather embarrassed to admit that it took me 4 tries yesterday. On attempt 3, I went with “BRACE.” In case you’re curious, I’m currently on a 239 day streak. And also, in case you’re wondering, I do them all: the crossword, the mini, spelling bee, and now connections. They’re all part of my morning ritual.

Words are fascinating things. That we play games with them like WORDLE is evidence of the power they have. They amuse and divert us; they hurt and heal us. They help to share our deepest thoughts and feelings; and are also woefully inadequate to express those thoughts and feelings. We are bombarded with words; we bombard others with words. And now, thanks to Chatgpt, we can use artificial intelligence to manufacture words for ourselves, for others, or for class assignments. You probably wouldn’t be surprised to learn that preachers are using AI to manufacture or produce sermons.

That’s quite an irony, isn’t it, given today’s gospel reading: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God.”

I said to a couple of people last night as they were expressing sympathy for me having to get up today and do this service, that for me, in many ways, as beautiful and powerful as the Christmas Eve services are, with choir, and carols, candlelight, and a full church, this service is the one that matters most to me—and it’s for one reason, that I have the great honor and privilege to proclaim this gospel text: John 1:1-14, and to preach the good news from it. Although I’ve preached on this passage more than twenty times, it will never get old; I will never exhaust its meaning, and I will never fully comprehend it.

In the beginning was the word. In principio erat verbum. En arche en ho logos. The Greek word behind our translation of word is “logos.” It means much more than “word.” In Hellenistic philosophy, it referred to the underlying order and reason of the universe and many scholars think that the author of the gospel, or the author of the hymn on which the gospel’s author was drawing, used another Greek word—sophia, or wisdom, which in Greek thought and in Jewish scripture, was the personification of wisdom. Because it is in the feminine gender it is thought, it was changed from “Sophia” to “Logos.”

But word, or reason, or order, or even wisdom points to something deeper. It’s not just that the Word, Christ, the Second Person of the Trinity was present at creation. It’s that God created through the Word, by speaking. As Genesis 1 states, “God said, ‘Let there be light.’ And there was light.

This is powerful stuff. There’s another image that I find particularly compelling. When the great Dutch humanist Erasmus went about publishing the first Greek New Testament, and then re-translating the Greek into Latin, he recognized the inadequacy of “word” as a translation of “logos.” So he chose another Latin word “sermo.” While it’s the root from which our word “sermon” comes, it actually means something quite different: “conversation.”

That image intrigues me. Erasmus is implying that at the heart of God’s nature, at the heart of the Trinity, is conversation, communication. I find it wonderfully reassuring that in spite of our experience of the inadequacy of words, and of communication, that in the Trinity, in God, there is perfect conversation, perfect communication.

Of course, all of that is fine theological speculation; much more than a word game, but also, in a way, a word game. To place Christ at the very beginning, in creation, the means of creation, is to say something or many things, about God’s nature, and about the nature of God revealed in Christ.

But our gospel goes further; our faith goes further. The majestic language, the lofty theological reflection that is revealed in the opening cadences of John 1: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God,” concludes, “And the Word became flesh and lived among us.”

That’s the message of the gospel, the message of Christmas. In fact, the Greek could be translated “tabernacled” or “tented” among us. Again, there are multiple meanings here. John is referring back to the way God was present among the Israelites during the Exodus, in a tabernacle or tent but there’s also a powerful sense, that he is alluding to the temporary, ephemeral nature of a tent. Like our bodies, tents are not permanent, they lack solidity; they are easily damaged.

That is to say, the word took on frail human flesh to be like us. But John goes on and in one of his key paradoxes, reminds us that in that temporary dwelling, we catch sight of God’s glory.

So we are back in Bethlehem, back in the confusing paradox that God became incarnate in a very ordinary way, in the poorest of circumstances, in the weakest of all human forms, a baby. And it is in that paradox, that we see God’s glory. For John, it is the same paradox as the cross, which he almost always refers to as the glorification of Christ. What he is telling us is that in these moments of weakness, we see God’s majesty and power.

But we have the reality of that incarnation before us in many ways. We see it, we taste it in the bread and wine of the eucharist, when we receive the body and blood of Christ. We see it in the very imperfect Church, both our local community, and the worldwide communion, bodies filled with flaws and imperfections, but also, mysteriously, the body of Christ. And finally, we may see it in ourselves, imperfect human beings though we are, but by the grace of God filled with the presence of Christ. May this Christmas rekindle in all of us the knowledge of Christ’s presence, of Christ’s glory, in ourselves, in our church and community, and in all the world.