November 11, 2012

Today is our Annual Meeting. I wouldn’t say it’s the highlight of the year but it is an opportunity for us to gather in fellowship, to reflect on the past year, and to begin planning for the next year. Today may be more anticipated than in other years because we will be joined today by architects who will share with all of us what they’ve learned about Grace Church, our ministries and our building over the last months as they work toward the development of a master plan for the future.

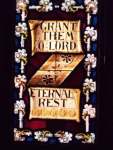

We are at the end of a week that has seen great excitement here in Madison and around the country. The election is finally over but there are serious issues facing our country and, more ominously, Republicans are already beginning to jockey for position in the 2016 race. Whatever we discuss today at our Annual Meeting, whatever our mood, our excitement and worry about the future of Grace Church, are overshadowed by these larger concerns and issues. A few of us will also have noticed that today is Veteran’s Day, for an earlier generation, Armistice Day. Some of us will be thinking of loved ones who served and perhaps died in the military; others may be thinking of their own service and those with whom they served.

The election laid bare some of the deep divisions in our society; divisions between rich and poor, progressive and conservative, divisions of race and ethnicity. Perhaps most tragically, the deep religious divide in our country seems to have widened and become more bitter. Although President Obama did have a small Catholic majority who voted for him, Roman Catholic Bishops and many prominent conservative Protestants threw their support behind Governor Romney. At the same time, Obama won a huge majority among the religiously unaffiliated.

We may want to think such trends have no affect on our congregation at Grace. Unfortunately, that’s not true. To the extent that our culture increasingly views Christianity as beholden to one political point of view and that the number of those who claim no religious affiliation is growing, our attempts to proclaim a gospel of God’s love and inclusion will fall on deaf ears. Our work will be more difficult.

Our lessons today confront us with the reality that God’s Word stands in judgment of our culture and society, our national conversations about the role of Christianity, our values concerning the poor and needy. I know that sounds presumptuous but to take these words seriously is to call into question all of what we value. The gospel first. We are in the last week of Jesus’ life. Mark gives a clear chronology and progression of what happens in these days. On the first day, Jesus enters Jerusalem to hosannas and palm branches. He goes to the temple, looks around, then leaves Jerusalem to spend the night in Bethany. The next days he spends in the temple, teaching, but also with a series of confrontations with the religious and political leadership of Jerusalem and the Temple.

In today’s Gospel, Jesus makes a comment about the scribes. They were the official interpreters of the law: consummate insiders “who like to walk around in long robes, and to be greeted with respect in the marketplaces, and to have the best seats in the synagogues and places of honor at banquets! They devour widows’ houses and for the sake of appearance say long prayers.” The contrast with the widow is obvious. While the scribes paraded around, she brought in two copper coins, all that she had. We could hold up these two brief stories as diametrically opposed opposites, the widow’s exemplary behavior over against the hypocritical scribes.

There’s another way of thinking about these two stories that derives from the context in which they appear. Jesus has been teaching in the temple; he has been confronting, and has been confronted by, representatives of the religious and political elite. He has just pointed out the hypocrisy of much of that religious leadership. He has castigated their pride and arrogance, alluded to their wealth. Immediately after the story of the widow’s offering, Jesus and his disciples leave the temple. As they go, the disciples remark on massive size and Jesus predicts its destruction. The widow’s offering, though praised by Jesus, could also be seen as an example of the temple’s oppression of the people. Impoverished, she still gave what she had as an offering.

The mosaic law, the Torah, insist that society take care of its weakest members—the widow and the orphan. The scribes, Jesus said, “devour” literally, “gobble up” widows’ houses. Whatever the scribes’ commitment to Torah, they were disobeying one of its central values.

In the story of the Book of Ruth, we see another example of the plight of widows in Hebrew society. We hear only a small part of that wonderful book in today’s reading; the celebration after a bountiful harvest and the marriage of the widowed Ruth with the wealthy Boaz.

It is a story about love and loss, about friendship and commitment, and about our responsibility to provide for the weak and defenseless.

A man and his wife move from Bethlehem to the neighboring country of Moab during a time of famine. They have two sons, and the sons marry Moabite women—one is named Ruth, the other Orpah. The man dies, leaving his wife, Naomi, a widow. Ten years later, the two sons die, leaving their wives childless. Naomi decides to return to Bethlehem since the famine is over, in hopes of finding refuge with relatives. She tells her daughters-in-law to remain behind, but one of them, Ruth refuses. The words she says are among the most familiar in all of biblical literature: “Wherever you go, I will go, wherever you lodge, I will lodge, your people shall be my people, and your God my God.”

So the two widows return to Naomi’s home of Bethlehem and try to scrape together enough food to help them survive. Naomi schemes to find Ruth a husband. We see that scheming in today’s reading. In fact, it’s almost an attempt at entrapment. Boaz doesn’t fall for it. This brief summary does little justice either to today’s reading or to the whole book of Ruth but it’s enough to underscore both the vulnerability of widows in the ancient world, and the biblical insistence on their protection.

We have heard a great deal in this election season and before about the 1% and the 99%; or the 47% who are takers, not makers. After the results became clear Tuesday night, outraged conservative pundits complained that we are now an America, a society, where the majority demands handouts.

I don’t care how you voted, if you voted on Tuesday. I don’t care if you celebrated or mourned the results of the election. What I care about, what the gospel cares about are the weak, widows and orphans, those left behind and ignored by our society and our economy. The God we encounter in Jesus Christ, the God who came to us in poverty and walked the dusty roads of Palestine, bringing hope and healing to those he encountered, calls us to minister to those who are in need, broken-hearted. Jesus Christ calls us to embrace those whose bodies and lives are broken by the unjust systems and economy in which we live. He calls us to see in those people, in the widow, orphan, homeless, and hungry; God calls us to see in their faces the face of Christ and to extend to them our love, a loaf of bread, and the hope of the world.